Belmont, North Carolina – The Abbey Basilica of Maryhelp

Abbot Leo Haid

1876 to present

In 1876, a German monk arrived in the most heavily Protestant county of North Carolina with instructions to undertake two seemingly incongruous missions: to spread the faith while founding a cloistered community. The story of his slow but steady progress toward both goals illuminates several aspects of 19th century American Catholicism.

In the 1870s, North Carolina had only several hundred Catholics in its population. Not coincidentally, among southern states it had the smallest percentage of foreign born. Along with Florida, it had the fewest Catholic churches in the South. A handful of priests tended to the Catholic population. Into this Catholic desert in 1876 came a German monk with the paradoxical mission of spreading the faith by starting a monastery. This venture, and the stories of some of those involved, illuminates several aspects of 19th century American Catholicism.

The Abbey Basilica of Maryhelp in Belmont, North Carolina. Photo by Ellen Tucker.

Catholicism in 19th Century America

Catholicism in the United States in the 19th century was largely immigrant and urban, which was why the South, more native born and rural, had fewer Catholics than other regions. The arrival of German and Irish Catholics had made Catholics the largest single religious group in the United States by the time of the Civil War, although they remained a small minority (about 7% of the total population) in a predominantly Protestant country. Catholic immigrants from eastern and southern Europe (Poles and Italians, for example) followed the Germans and the Irish, increasing the Catholic population by 1900 to about 17% of the total, keeping Catholics the largest religious group but still a small minority. This remains the case, as Catholics currently make up about a fifth of the American population.

Minority status amidst an often hostile Protestant majority led the Church to establish a robust separate institutional life. (Historians argue that there was actually less anti-Catholicism in the South, where there were fewer Catholics and where the Democratic Party dominated—Catholics being an important part of the party nationally.)[1] Parochial schools, for example, developed as an alternative to public schools that reflected dominant Protestant views and principles.

A Protective Separatism that Fostered Suspicion

This protective separatism led to suspicion among the majority that Catholics were not quite American, more loyal to the Pope and their Church than to America. In the later decades of the 19th century, many states passed constitutional amendments prohibiting the expenditure of public money on private sectarian or parochial schools. In 1922, the voters of Oregon passed an initiative requiring attendance at public schools, a law ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1925 (Pierce v. Society of Sisters). The Courts revisited the issue of public funding for religious schools repeatedly in later years, most importantly perhaps in Everson v. Board of Education (1947).

The Organization of a Catholic Mission Field

Book jacket of Cardinal James Gibbons’ popular account of the Catholic faith, written for American readers. Courtesy Amazon.

Growth through immigration led the American church hierarchy to propose and Rome to approve the creation of additional dioceses (each an area of administration under a bishop, who then organizes and is responsible for parishes within it), as well as what the Church calls apostolic vicariates. The latter are areas in which there are too few Catholics to warrant a diocese. Such areas, which are essentially fields of mission work, are the responsibility of an apostolic vicar. North Carolina became a vicariate apostolic in 1868. James Gibbons (1834-1921) became the first apostolic vicar, and in subsequent years as the second American elevated to the rank of Cardinal, the most prominent Catholic Churchman in America. He traveled widely across the state meeting with Catholics and Protestants alike. He spoke in Protestant churches, collecting his talks in Faith of Our Fathers, the most popular presentation of Catholic teachings published during these years.

Gibbons was not the only missionary working in North Carolina. Father Jeremiah O’Connell, a member of the Order of Saint Benedict, a Catholic Monastic order, served as an itinerant preacher in North Carolina after the Civil War. He conceived the idea of starting a monastery and school in the state. Amidst distressed economic conditions after the war, he was eventually able to purchase farmland in the piedmont, just west of Charlotte, North Carolina. He persuaded his Benedictine colleagues at St. Vincent Abbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania to undertake the mission. The first monk from St. Vincent’s arrived at the new site, now in Belmont, North Carolina, in 1876.

The Reluctant but Effective Founder of a Mission to North Carolina

This photo of Leo Haid, O.S.B., was included in a 1914 Catholic Church publication intended to celebrate the golden jubilee of Pope Pius X. By this time Haid was both Abbot Nulius of Belmont Abbey and Vicar Apostolic of North Carolina.

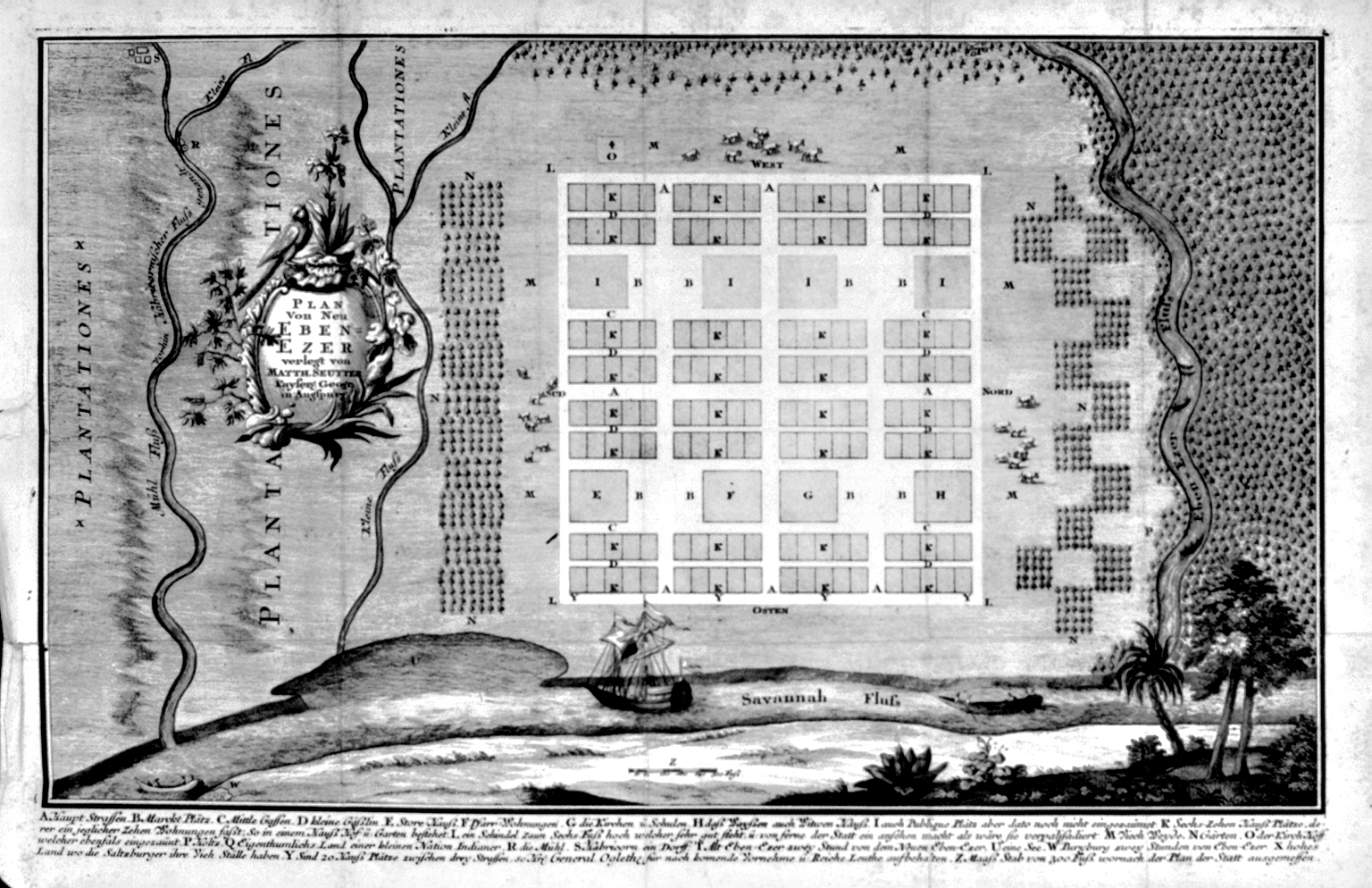

St. Vincent’s Abbot, Boniface Wimmer, had enthusiastically pursued missionary activity in America. He planned for the North Carolina site, named “Maryhelp,” to take controlling authority over the already successful establishments in Savannah, Georgia to the south and Richmond, Virginia to the north. Persuading Vatican authorities to support his plan proved easier than recruiting an Abbot for the post, which would be situated in the most predominately Protestant area (Gaston County) of the most predominately Protestant state in the nation. In 1885 he orchestrated the election of Father Leo Haid, a 37-year-old second-generation German American Catholic with a gift for teaching that would prove valuable at Maryhelp, where Abbot Wimmer intended to found a college and seminary.

Devoted to his monastic life and teaching work at St. Vincent’s, Haid accepted the North Carolina mission out of duty, and proceeded to impose the highly structured Rule of Benedict on his small community of ten monks. He soon came to be recognized as a capable leader, and in 1888 was appointed Vicar Apostolate of North Carolina, while being allowed by decree of Pope Pius X to continue as abbot of the growing abbey, now named Belmont. He was the only ecclesiastic in the US to be accorded this double honor, which brought him responsibility for establishing and managing churches not only in the surrounding area but throughout North Carolina. The Abbey’s jurisdiction over nearby Catholic churches would continue until the Diocese of Charlotte was established in the 1970s.

This photo (by Rnrivas, May 2016, Wikimedia Commons) shows an aerial view of the Abbey Basilica of Maryhelp and Belmont Abbey College campus. The college, originally called St.Mary’s, was founded in 1876, when the first Benedictine monks arrived, accompanied by two students, and began building simple classrooms, lodgings, and a sanctuary building. Today, Belmont Abbey College is distinguished by its beautiful gothic architecture. With an enrollment of about 1500 students, it is the only Roman Catholic-affiliated college in North Carolina.

[1] Woods, 355