Christian Progressives Respond to Urban Poverty: Jane Addams on Social Settlements

1892

125 years ago this summer, Jane Addams wrote a seminal essay announcing a vision of civic life and Christian idealism that had moved her and other reformers to found “settlement houses” in poor urban neighborhoods.

Christian Progressives Respond to Urban Poverty: Jane Addams on Social Settlements

In “The Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements,” written 125 years ago this summer, Jane Addams explains the combination of civic, social, and spiritual motives leading reformers of her generation—particularly women reformers—to found “settlement houses” in poor urban neighborhoods. When Addams wrote the essay, the Hull House settlement in Chicago that she and Ellen Gates Starr founded was not quite three years old, and many of the innovative programs it would offer had not yet been established. Yet the essay reverberates with the author’s excitement at having found, after prolonged search, the best possible use for her idealism and energy. Written as a lecture to those attending a summer school of the Ethical Culture Society, it purports to speak for a generation of highly educated, privileged young women who found themselves without work or purpose.

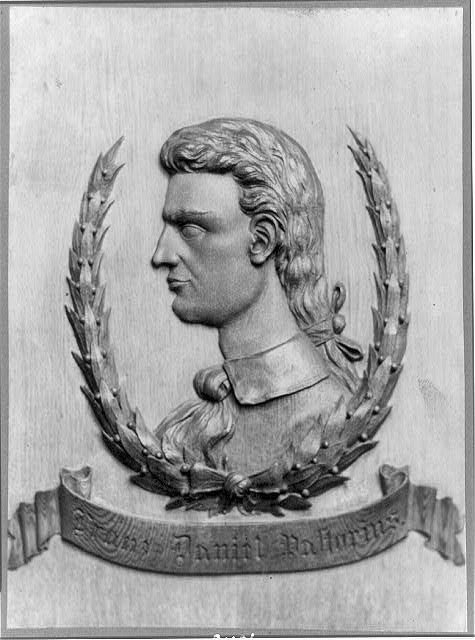

Jane Addams, Library of Congress

The Education of Jane Addams

This was certainly Addams’ story. The daughter of a Quaker active in Illinois Republican politics, Addams was raised to feel a civic duty for which, as a woman, she found little active outlet. At Rockford Female Seminary (where Addams earned one of the first bachelor degrees the college granted), she was steeped in an atmosphere of Christian idealism and urged to enter the field of foreign mission. Resisting this, she found that the alternative career expected of her was attending to the domestic happiness of her widowed stepmother and stepbrother.

It took her eight years, during which she traveled in Europe with her college friend Ellen Gates Starr and visited the original settlement house—Toynbee House in London—to discern an independent course. In 1889 she decided to use her inheritance to move with Starr to an industrial neighborhood of Chicago, establishing residence in a former mansion now surrounded by cheap tenements crowded with immigrants recently arrived from Italy, Germany, Bohemia, and the Jewish ghettos of Eastern Europe. Addams and Starr outfitted the home with elegant but practical furniture and decorated the walls with art they had collected in Europe, and then set out to meet their neighbors. Their simple plan was to learn from these neighbors how they might help them in their struggle to gain a foothold in American society.

Addams would never look back. Firm of purpose, yet open to what others could teach her, she inspired a succession of activists who found support in Hull House for a range of projects to reform labor practices, juvenile justice, education for both children and adults, public health and sanitation, and other areas of urban life.

A Progressive Reform Based on Early Christian Communalism

Unusually for a movement manifesto, “The Subjective Necessity of Social Settlements” articulates deeply personal motives. Yet it unites these with reflections on psychosocial, civic and spiritual life. Indirectly commenting on the Darwinian view of human evolution then sweeping American intellectual life, Addams asserts that prosperous moderns carry some memory of their ancestors’ struggle against starvation, and that this memory seeks to be channeled into fellow feeling with the poor. Seeing American demographics being reshaped by massive immigration from Catholic and Jewish Europe (viewed warily by Protestants who saw them as uneducated peasants lacking a cultural disposition to self-government), Addams reasons that, “if in a democratic society nothing can be permanently achieved save through the masses of the people, it will be impossible to establish a higher political life than the people themselves crave.” Hence, “the good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain . . . until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into our common life.”

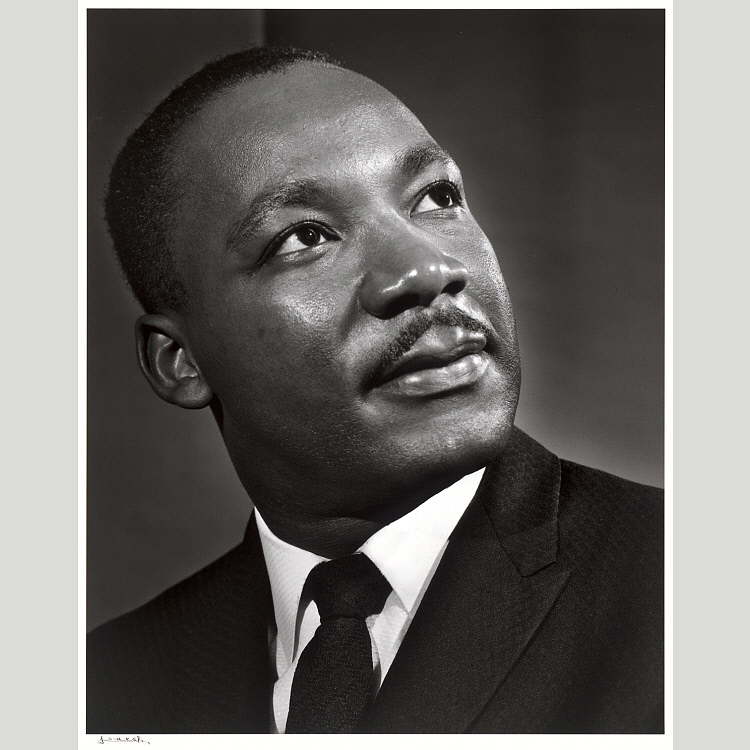

Addams with the children of Hull House

Addams then speaks of the ultimate human purposes that inspire religious faith. She hails what she calls a “renaissance” of the humanitarian ideals of early Christianity. Before the faith was codified as a “religion” opposed to other religions, it was “a command to love all men, with a certain joyous simplicity. . . . The spectacle of the Christians loving all men was the most astounding Rome had ever seen. They were eager to sacrifice themselves for the weak, for children and the aged. They identified themselves with slaves and did not avoid the plague. They longed to share the common lot that they might receive the constant revelation,” that is, “the joy of finding the Christ which lieth in each man, but which no man can unfold save in fellowship.” Those who joined the settlement house movement would gain from it as much as they gave.

A reproduction of the dining room at Hull House, Hull House Museum, University of Chicago

Precepts to Guide the Settlement House Movement

From these motives for founding a settlement house, Addams moves to the principles that must govern the experiment. It cannot espouse a particular political stance, but must “give the warm welcome of an inn to all such propaganda, if perchance one of them be found an angel,” she says, alluding to Hebrews 13:2. “The one thing to be dreaded in a Settlement is that it lose its flexibility . . . its readiness to change its methods as its environment may demand.” Paradoxically, residents of a settlement house must develop convictions while maintaining “a deep and abiding sense of tolerance.” They must practice “a scientific patience in the accumulation of facts” while opening themselves to emotional sympathy with those they live among, since through such sympathy one learns more about one’s fellows than a clinical detachment allows.

Addams’ leadership of Hull House was based on these precepts. Her flexible but determined leadership stood behind four decades of Hull House reformers as they worked to improve living conditions for the poor in Chicago and across the nation.

Citation

Victoria Bissell Brown, “Introduction: Jane Addams Constructs Herself,” in Twenty Years at Hull-House by Jane Addams, edited by Brown (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999)

Jean Bethke Elshtain, “Introduction: ‘The Snare of Preparation’ and the Creation of a Vocation,” in The Jane Addams Reader, edited by Elshstain (New York: Basic Books, 2002)

Louise W. Knight, Jane Addams: Spirit in Action (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010)