Ebenezer Baptist Church

Atlanta, Georgia

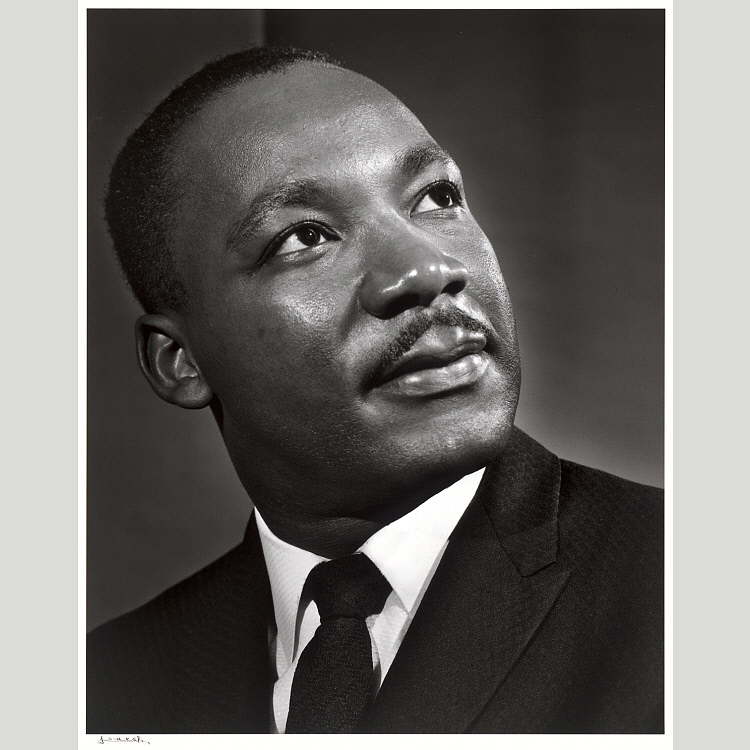

Founded during Reconstruction, Ebenezer Baptist Church served not only as a place of worship and community for Atlanta’s newly freed black population, but also as a hub of black resistance to segregation and racial oppression, This aspect of the church’s identity grew over the course of the early twentieth century, and became an especially prominent element of its mission when it called Martin Luther King, Jr. (son of the church’s senior pastor) to serve as co-pastor with his father in 1960.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Prophetic Voice in American Politics

Interior, view from the balcony. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site, Ebenezer Baptist Church, 407 Auburn Avenue Northeast, Atlanta, Fulton County, GA. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. HABS GA,61-ATLA,54–1

The name of the church is a reference to 1 Samuel 7:12 in which the prophet Samuel is recorded as raising a monument to the Lord in gratitude for His presence with Israel during their battle with the Philistines. An “ebenezer” thus became tangible reminder of the providence of God. Similarly, church buildings in black communities offered both physical and spiritual shelter to their congregations, a reminder that God’s work in their community was not yet finished.

Churches like Ebenezer Baptist played a central role in the black community during the period between the end of the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement, as seen in Millard Owen Sheets’ mural Religion at the Main Interior Building in Washington, D.C.

Martin Luther King, Jr.: Christianity and Social Justice

Within the African-American church community, such hope often found expression and support in the Social Gospel movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Proponents of the Social Gospel emphasized the practical dimensions of Christ’s ministry to the poor and downtrodden in society, as well as the Bible’s overarching message of justice and mercy. As the son, grand-son, and great-grandson of Baptist preachers committed to the Social Gospel movement, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s theology from the beginning was shaped by reflection on the practical as well as the pietistic. King would borrow heavily from the Social Gospel tradition, using his national platform to speak with a prophetic voice against the racial and class injustices he observed.

MLK, Jr. Interview on Look Here, 27 October 1957 presented by NBC News Time Capsule on Hulu

Although King’s denunciations of injustice were forceful, he maintained a life-long commitment to peaceful protest. In this television interview given three years prior to his sermon Can A Christian Be A Communist?, King discusses the influences on his understanding of Christian conscience and dissent, including what he refers to as “Ghandi-ism.” In what ways does this earlier, more conversational discussion of the necessity for African American Christians to assert themselves as actors within the civil sphere prefigure the themes of King’s later statement?

The hymn Jesus is Tenderly Calling, by Franny Crosby & George Stebbins, #229 in the Baptist Hymnal (1956) is referenced by King at the end of his sermon Can A Christian Be A Communist?. In what ways might the lyrics, with their emphasis on the response of the individual to the “call” of Christ have served to motivate King’s listeners?