Ebenezer, GA

1734 - Present

A Lutheran Refuge

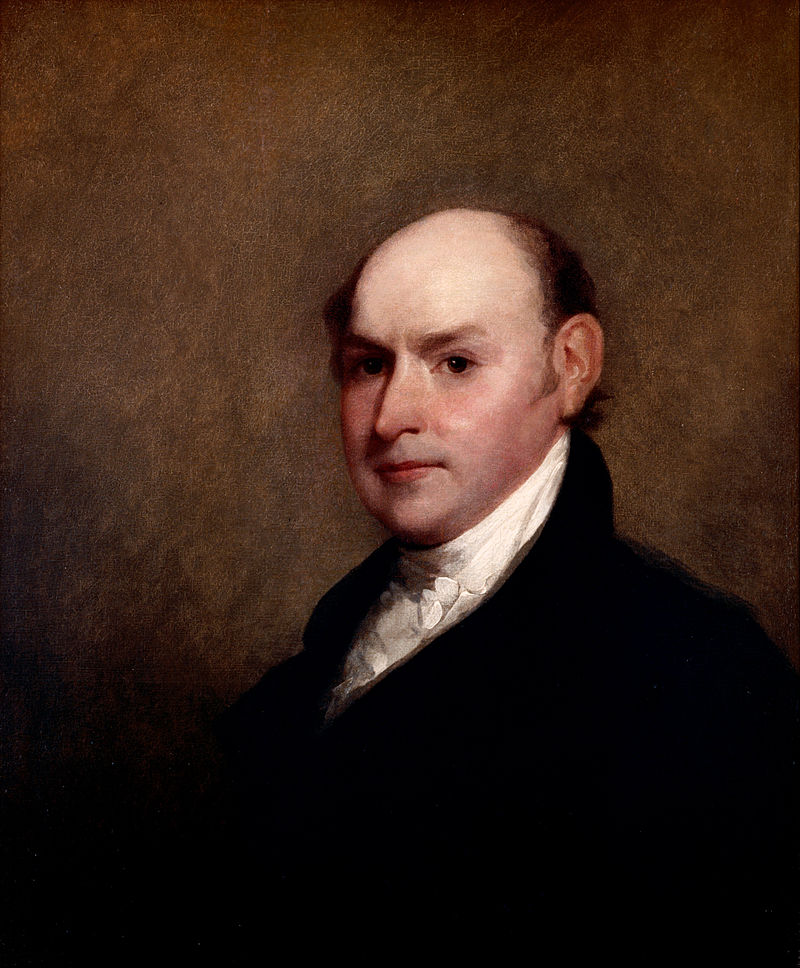

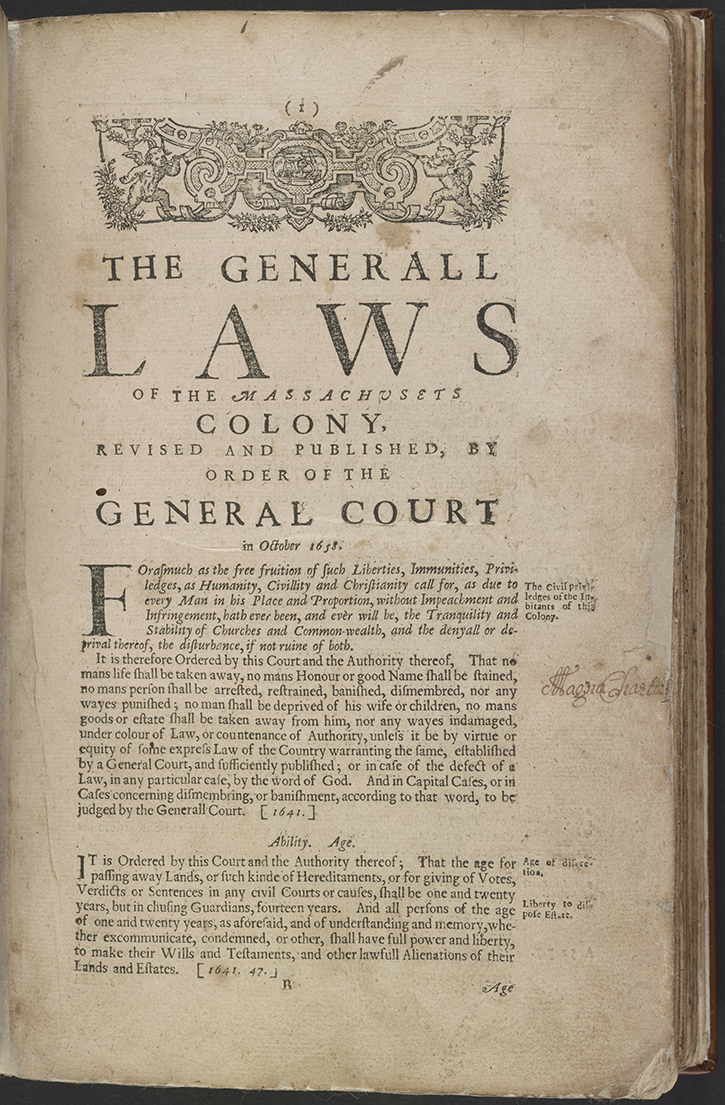

Engraving of Johann Martin Boltzius, c. 1754 – 1767. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-57323.

Following the expulsion of nearly 20,000 Lutherans from the Salzburg region of Austria-Germany in the early 1730s, the utopian founder of the colony of Georgia, James Oglethorpe, invited the displaced protestants to settle just outside the colonial capitol of Savannah. While only a small number of the refugee families choose to accept Oglethorpe’s offer, their impact on the early development of the region was significant, for the Salzburgers were an industrious lot whose commitment to the principles of Lutheran pietism made them ideally suited to the charity-driven community Oglethorpe hoped to model.

Led by their newly recruited pastor Johann Martin Boltzius (1703 – 1765)—the first group of migrants arrived in the colony in 1734. Oglethorpe gave the colonists a large tract several miles inland from the Savannah River, a location he chose for its strategic position as a barrier between the native population and the English settlements in and around Savannah. When they moved into the area, the Salzburgers named their community Ebenezer, an allusion to the biblical “stone of help” raised by Samuel to mark the Israelites miraculous victory over the Philistine army (1 Samuel 7:12).

Unfortunately for the Salzburgers, this initial settlement proved to be nearly impossible to farm and unhealthful, due to the sandy soil and nearly stagnant nature of the colony’s only water supply. Functioning as both spiritual and temporal leader for the community, Boltzius met on several occasions with Oglethorpe, urging him to allow the Salzburgers to relocate the settlement on the fertile banks of the Savannah River. He recorded these conversations in his “secret diary,”[1] where he framed the dilemma in eternal terms:

The removal to a fertile location also concerns the glory of God and of our Redeemer Jesus Christ, for 1) the Salzburgers have often had to hear the reproach from evilly disposed people that they do nothing but eat and pray, which reproach would not decrease but rather increase if they had to fetch their provisions from the store house. 2) How tickled and pleased the Papists and other enemies would be if they heard about the Salzburgers’ unhappy settlement. On the other hand, what heartbreak, sighs, laments, and disquiet the report of their distressing circumstances would arouse in the hearts of our spiritual and physical benefactors.[2]

Although Oglethorpe claimed to be sympathetic to the Lutherans as coreligionists, he was unmoved by these arguments and unwilling to agree to the relocation of the settlement at first, citing vague concerns about breaking his treaty with the native population as well as a less than noble desire to keep the German Lutherans geographically segregated from the English part of the colony. Instead, the proprietor suggested a compromise plan in which the town of Ebenezer would remain in its original location, but the community members would be given additional land grants farther away from their town dwellings to be used for growing crops. This Boltzius rejected outright, fearing that such a dispersal would have deleterious effects upon the “spiritual welfare” of the community, which centered upon their shared spiritual life. Boltzius’s diary reveals that the Salzburgers enjoyed a vibrant and committed spiritual community, gathering together for daily evening prayers, in addition to their two more formal services on Sundays.[3]

Boltzius resented Oglethorpe’s resistance to the idea of relocation, yet remained optimistic that the proprietor would eventually come around and honor his “fatherly” obligations to the immigrant community to whom he had promised a place of refuge. In his diary, he wrote “We still hope that the Salzburgers will enjoy the rights and liberties of Englishmen as free colonists,” but added despondently, “It appears to me and to others that the Salzburgers and the Germans in general are a thorn in the eyes of the Englishmen, who would like to assign them land that no one else wants and on which they will have to do slavish work.” Boltzius’ suspicions were confirmed when he received word that Oglethorpe had agreed to settle a group of Moravians near the Lutheran Salzburgers simply because of their shared ethnicity: “But in this way such confusion and disturbance would arise in religious affairs in this country as they have in Pennsylvania.”[4]

Urban Planning and other Utopian Dilemmas

Finally, in 1736, Oglethorpe relented and allowed the Salzburgers to move together as a community to a plot of land along the Savannah River. There, with Oglethorpe’s agents, Mssrs. Vat and Von Reck, they laid out the town on a grid pattern, with kitchen garden plots and more intensive agricultural fields arranged around the outskirts of the town (see map). The Salzburgers’ trials were not yet over, however, for when Vat and Von Reck saw the placement of the homes within the lots, they complained to Boltzius that “those huts that…were not built on the right corner of their lots would have to be torn down.” Incensed, Boltzius refused the order, whereupon Mr. Vat then went directly to the people, telling them “all their work on their huts and gardens were in vain because the houses had to be relocated, and in this he tried to give his words an appearance of reality.” Boltzius—resentful of this attempt to circumvent his authority, and grieved for his congregants who “were worried and distressed by this report”—used his pulpit to offer counsel in this instance.

I tried to encourage them both privately and publicly in the evening prayer-hour (although, as is always the case, only in more general terms and by referring to Holy Writ). On this occasion it occurred to me that the builders of the city of Jerusalem were frightened by threats and by contrary tidings. See Nehemiah 6: 5-7, 9-13.”[5]

Notes

[1] In contrast to his public diary, which he sent back to Lutheran authorities in Germany to both recruit additional colonists and maintain the chain of pastoral oversight. Return

[2] Secret Diary, 85. Return

[3] Secret Diary, 83. Return

[4] Secret Diary, 92, 95. Return

[5] Secret Diary, 92, 95. Return

Citation

Boltzius’s “secret diary” is reprinted in George F. Jones, “The Secret Diary of Pastor Johann Martin Boltzius,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 53, no. 1 (1969): 78-110.