Emma Lazarus, Poet of Exiles

1849 - 1887

Dedicating the Statue of Liberty on October 28, 1886, President Grover Cleveland thanked the French for their gift. Light from Liberty’s torch would “pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression, until liberty enlightens the world,” he said. This expressed the original idea for the statue. Yet the poet Emma Lazarus would cause Americans to see a larger message in it.

When the Statue of Liberty was officially dedicated on October 28, 1886, President Grover Cleveland made a short speech thanking the French for their gift. Concluding, he said:

We will not forget that Liberty has here made her home; nor shall her chosen altar be neglected. Willing votaries will constantly keep alive its fires, and these shall gleam upon the shores of our sister republic [France] . . .. Reflected thence, and joined with answering rays, a stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression, until liberty enlightens the world.

President Cleveland’s remarks were in keeping with the original idea for the statue. Yet a few other Americans—notably, the poet Emma Lazarus—saw the statue as conveying an additional message.

The Original Idea for the Statue

French historian Eduoard de Laboulaye, observing the close of the American Civil War, proposed that the French make a gift of a monumental sculpture to the United States. The gift would commemorate the success of American democracy. Laboulaye, a leading expert on the American Constitution and an abolitionist, understood the war as Lincoln did. Before a worldwide audience, the war had tested whether a nation “conceived in liberty, and founded on the proposition that all men are created equal . . . can long endure.” Laboulaye saw the statue as a joint project of France and the United States, one that would rebuke the authoritarian impulses of Louis Napoleon, who had staged a coup d’état in 1851, reinstated the empire, and imposed on France a new constitution granting himself almost dictatorial powers. By 1865, however, Louis Napoléon had permitted a return of a parliamentary system, allowing Laboulaye to push his idea.

Raising the Funds

Albert Fernique, Workmen constructing the Statue of Liberty in Bartholdi’s Parisian warehouse workshop, ca. Winter 1882. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division,LC-USZ62-20113.

Ten years later, after Louis Napoléon had fallen from power during the Franco-Prussian War, Laboulaye was able to initiate a project. In September 1875 he announced the formation of the Franco-American Union as a fundraising platform for it. His friend, French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, had drawn designs for a colossal statue of a robed woman bearing a torch, to be called “Liberty Enlightening the World.” The French people, he hoped, would donate the money for the statue and the American people would finance the building of a pedestal for it.

It took creative effort in both countries to raise the money for the project. One of many efforts in New York City, the 1883 “Art Loan Fund Exhibition in Aid of the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund for the Statue of Liberty” elicited a contribution from Emma Lazarus. Her poem “The New Colossus” was read at the opening of the fund-raising exhibit and published to acclaim in the New York World and New York Times.

The Poet Who Reframed the Statue’s Meaning

The poem’s title alluded to the long-since vanished Colossus of Rhodes, a representation of the Sun-god Helios erected in 280 BC, whose reputed height Bartholdi had matched in his design. The new statue, Lazarus wrote, would displace the ancient emblem of conquest with an emblem of welcome. But Lazarus’ poem also shifted Laboulaye and Bartholdi’s thematic emphasis. Instead of “Liberty Enlightening the World,” Lazarus called the statue “Mother of Exiles.” The beacon Liberty raised did not simply illuminate the virtues of free government for the edification of the non-free world; it guided the downtrodden toward shelter:

Jet Lowe, View west of Statue of Liberty, 2009. Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, HAER NY,31-NEYO,89–295.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates[1] shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning,[2] and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.[3]

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Poet James Russell Lowell, then American Ambassador to Great Britain, wrote Lazarus that she had finally supplied a “raison d’être” for the statue, and that, in fact, he liked the poem better than the statue itself.

By 1886, however, the brief stir made by Lazarus’ poem had subsided, and the dedication ceremony highlighted the ideal of constitutional democracy Laboulaye intended the statue to commemorate. The poem was not read, nor the young poet present, at the ceremony. Lazarus, who had gone abroad hoping to find relief for failing health, died the next year. Reconceiving the statue as a symbol of American openness and generosity, Lazarus had asserted an ideal not always in accord with Americans’ attitudes towards new waves of immigrants. Most of those immigrating to the United States in the latter half of the 19th century spoke no English, observed religions outside of the Protestant mainstream, and competed in the major cities with those already resident for rapidly changing industrial jobs and hastily constructed housing.

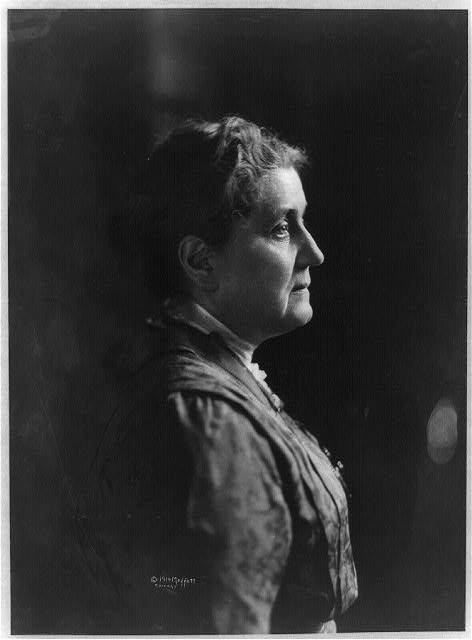

Lazarus’ Poetic Evolution

Lazarus herself, however, by the time she wrote “The New Colossus,” had become an outspoken advocate for Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia and arriving in New York. This marked an evolution in her self-understanding. Born in 1849 into a prosperous Sephardic[4] Jewish family who had settled in New York prior to the Revolution (Moses and Gershom Mendes Seixas were her maternal great-uncles[5]), Lazarus grew up with a subdued awareness of her family’s religious traditions. Her parents observed only the major Jewish holidays, ignoring the daily prayer traditions.

Emma Lazarus, engraved by Thomas Johnson; photographed by William Kurtz. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs, LC-USZ62-53145.

Lazarus spent her girlhood reading literature in several languages, translating and imitating 19th century German poets on her way to finding her own poetic voice. Rather than the cadences and attitudes of Jewish prayer, she absorbed Christian literary styles and themes. However, when she read Heinrich Heine, a German Jewish poet, she found his conversion to Lutheranism troubling. This awakened her interest in her own Jewish heritage and in the Hebrew poetry of the Bible.

In 1881, she became aware of the Jewish refugees’ plight. She began visiting a shelter for Jewish refugees on Ward’s Island established by Jewish philanthropist Jacob Schiff, eventually publishing a critique of its unsanitary facilities. She became involved in efforts to teach the refugees English, give them job training, and find them employment. She also began writing a column for the American Hebrew, provocatively titling it “Epistle to the Hebrews” (alluding to a letter of St. Paul). While faulting European Christians for causing the refugee problem, she implicitly accused the long-established American Sephardic community for inattention to the problems of the Ashkenazy[6] Jewish newcomers.

Lazarus’ Ambivalent Jewish Identity

Lazarus was the first serious American poet to speak with an avowedly Jewish voice. Yet biographer Esther Schor argues persuasively that Lazarus’ poetry expressed a dual ethnic and national identity. Although secular in her habits, her study of Jewish Hebrew scripture opened her to what Schor calls the “prophetic and ethical burdens of Judaism.”[7] It drew her to defend a tradition that had been heroically maintained despite two millennia of anti-Semitic persecution. In one attitude, Lazarus portrayed America as a secure haven of liberty for the religiously oppressed. In another, she worried that the Jews could never be secure until they established their own Jewish state. She advocated the settlement of Jews in Palestine at least a decade before Zionism became a recognized cause.[8]

A signed copy of the Alhambra Decree, or Edict of Expulsion, issued on March 31, 1492, by Isabella I of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragon, ordering all practicing Jews to leave Spain by the end of the following July (Wikimedia Commons).

In the same year that Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus,” she wrote another sonnet, “1492.” This poem views the European arrival in America through a double lens. Columbus’ first voyage occurred in the same year that Ferdinand and Isabella issued the Alhambra decree, expelling the Jews from Spain. Lazarus celebrates the fortunate coincidence—the tragic expulsion and the discovery of a new world that would welcome Jews without prejudice—silently passing over the two centuries that elapsed as the exiles moved to Portugal, then to Holland or England, then to New World ports in Barbados or Brazil, before finding a safe harbor in North America:

Thou two-faced year,[9] Mother of Change and Fate,

Didst weep when Spain cast forth with flaming sword,

The children of the prophets of the Lord,

Prince, priest, and people, spurned by zealot hate.

Hounded from sea to sea, from state to state,

The West refused them, and the East abhorred.[10]

No anchorage the known world could afford,

Close-locked was every port, barred every gate.

Then smiling, thou unveil’dst, O two-faced year,

A virgin world where doors of sunset part,

Saying, “Ho, all who weary, enter here!

There falls each ancient barrier that the art

Of race or creed or rank devised, to rear

Grim bulwarked hatred between heart and heart!”

Even more than “The New Colossus,” this sonnet affirms Lazarus’ pride as an American and her faith in the American guarantee of religious freedom. Yet it also depicts the immigrant Jews more heroically than she had in “The New Colossus,” where she called them “the wretched refuse” of an overcrowded Europe. Here they are “the children of the prophets of the Lord.”

Restoration of “The New Colossus” in the National Understanding of the Statue

The Statue of Liberty from Ellis Island, U.S. immigration station in New York Harbor, a small boy shows his parents the Statue of Liberty, ca. 1930. Photographer unknown. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-03375.

In the national imagination, Lazarus’ sonnet about the Statue of Liberty eventually eclipsed both Laboulaye’s intent for the monument and Lazarus’ own uncertainty about America’s commitment to religious freedom. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Lazarus’ friend Georgina Schuyler worked to have “The New Colossus” memorialized on the Statue of Liberty. In 1903 it was cast in bronze and mounted on the inner wall of the pedestal. In the 1930s, when large numbers of refugees began fleeing fascist Europe and immigrating to the United States, the poem was remembered and quoted in speeches—and even a Hitchcock movie, Saboteur, during the second World War. Irving Berlin set it to song in his 1949 musical Miss Liberty. In 1986 the poem became a featured display in the museum through which most visitors to the statue pass.

Notes

[1]The mouths of the Hudson and East Rivers.Return

[2]The Statue’s torch was lit with electricity, using Edison’s recently patented invention of a light bulb that entrapped and prolonged the light of a burning filament.Return

[3]The Statue of Liberty was erected on Bedloe’s Island, situated in the harbor that divides Brooklyn from what in the 1880s was New York City (Brooklyn was consolidated into the city as one of its boroughs in 1898).Return

[4]Sephardic Jews descend from those expelled from Spain and Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century.Return

[5]Esther Schor, Emma Lazarus (New York: Schocken Books, 2017), p. 5 – 6. Moses Seixas, as lay leader of the Touro Synagogue at Newport, Rhode Island, delivered in 1791 the speech of welcome to visiting President George Washington that prompted Washington’s eloquent promise of freedom for religious minorities, the Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport. Gershom Mendes Seixas was pastor of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel at the time of the Revolution and an outspoken supporter of the Patriot cause.Return

[6]Ashkenazy Jews descend from those who settled in Northern and Eastern Europe.Return

[7]Schor, p. 210.Return

[8]Schor, p. 155.Return

[9]An allusion to Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, passageways and doors. He is depicted as having two faces, one looking toward the exited space, or the past, and the other toward the space to be entered, or the future.Return

[10]Here, “the West” refers to Western Europe and “the East” to Eastern Europe.Return