Princeton, New Jersey

1746 - Present

The sister-institutions of Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey) and later, Princeton Theological Seminary have been at the center of American Presbyterian education and scholarship.

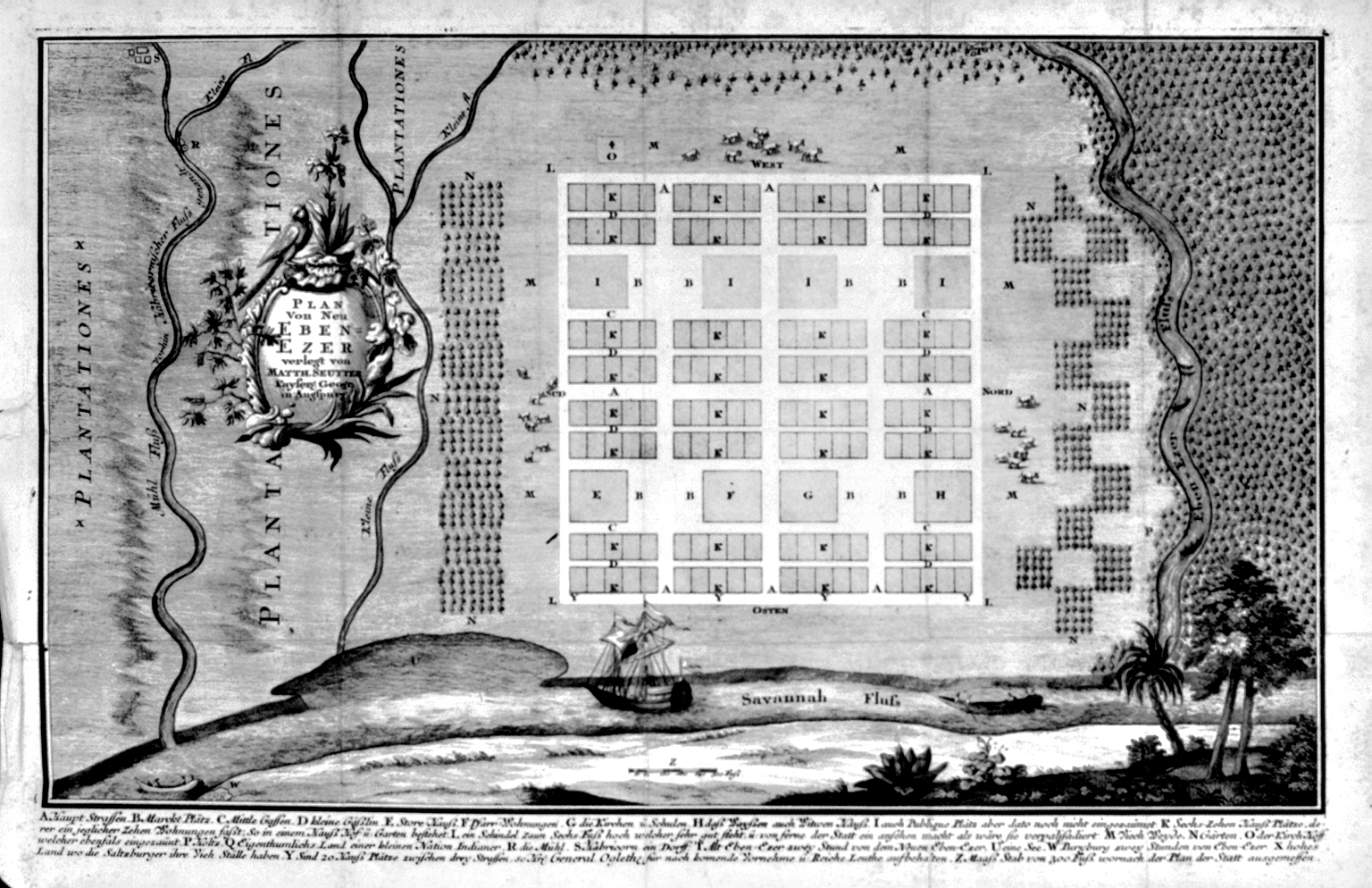

Frontispiece to Gilbert Tennent, An Account of the College of New-Jersey (Woodbridge, N.J., 1764). New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7acf-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

A Home for Presbyterian Evangelicalism

Founded in 1746 to provide training for New Light (evangelical) ministers during the Second Great Awakening, the College of New Jersey moved into Nassau Hall (shown right, from a sketch drawn by Gilbert Tennent) in 1756. Ministerial training ceased to be the primary goal of the college after John Witherspoon was named to the presidency in 1768, although Princeton retained a strong evangelical identity and connection to American Presbyterianism until the end of the nineteenth century.

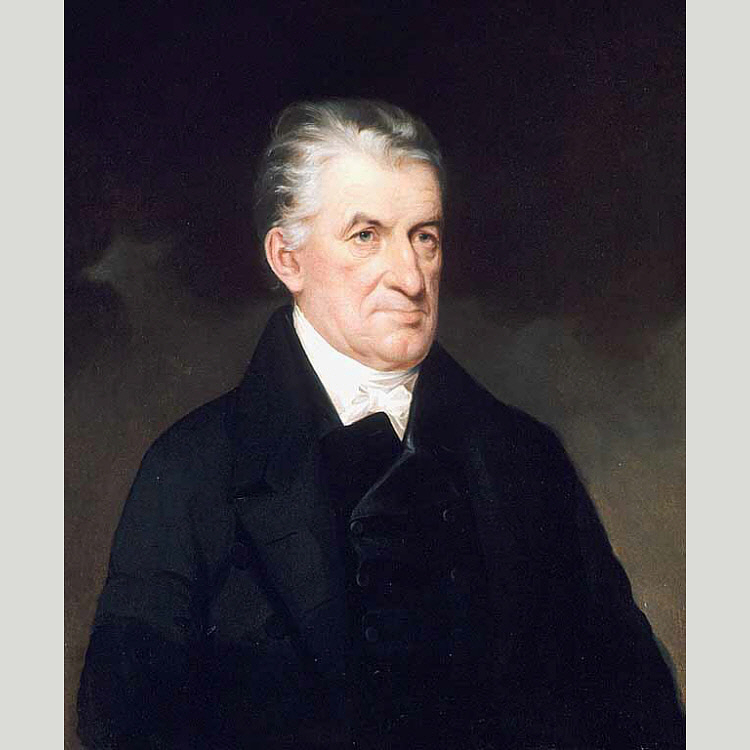

As the curriculum at Princeton became more broadly academic, it became apparent that a new institution where ministerial candidates could go to obtain specialized theological training was needed. Accordingly, in 1809, the Presbyterian Church in the United States voted to establish a seminary where students might be taught in accordance with the great creeds and confessions of Presbyteriansim. Naturally, given Princeton’s long-standing associations with American Presbyterianism, as well as its desirable location in the mid-Atlantic, the denomination hoped to be able to locate their new seminary near the existing college. In 1811, the General Assembly reached an agreement with the new president of Princeton, Ashbel Green, in which the college ceded a portion of its land to be used to create the campus for the new seminary and pledged to accommodate the seminarians in its own buildings until construction of the theological school could be completed.

John Frelinghuysen Hageman, History of Princeton and its institutions (J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1879), 324.

Relations between the seminary and the college remained close for almost a century; indeed, Charles Hodge, professor and second president of the seminary served as a member of the college’s Board of Trustees from 1850-1878, where he used his influence to help keep religious instruction central to the college’s mission and curriculum. Professors at one institution were regularly invited to give lectures at the other, and together, the College and the Seminary combined to offer the nation a model of excellent, religiously-influenced education with a strong orientation towards public service as an expression of personal piety.

At the seminary, Archibald Alexander and his successors in the theology department over the next century–Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander Hodge, and B.B. Warfield– developed this general attitude towards life and learning into a unique strain of Reformed evangelicalism, eventually known as “the Princeton school.” Characterized by a combination of robust scholarship and strict confessionalism with “concern for religious experience [and] sensitivity to the American experience,” for over a century, Princeton theology epitomized orthodox Christian scholarship in America.1 The writings of Princeton theologians, were not limited to academic audiences, but were widely distributed throughout the country in both book and article form. Through their students’ ministries and their own writings, Princeton’s theologians aimed at cultural transformation in the name of furthering Christ’s kingdom on earth, while simultaneously adhering to the most rigorous standards of academic scholarship.

The Clash of Cultures: Christianity and Liberalism

All of that changed in the 1900s, when the college and the seminary both fell under the influence of liberal, secularizing scholarship. In response, J. Gresham Machen, an esteemed professor at Princeton Theological Seminary published Christianity and Liberalism in 1923. Machen’s book undertook a defense of orthodox Christian doctrine against what he saw as the tendency of American Protestants to water-down the gospel in search of the elusive and transitory goals of relevance and ecumenicism. (Machen had been one of the most vocal opponents of an earlier attempt to unify the nation’s Protestant denominations into one “Organic Union” on the grounds that such an agreement, aimed at the “consolidation… of particular churches” into one generic and doctrinally imprecise ‘church’ was both impractical and unbiblical; see “Protestant Churches Make Plan For United Action,” Scarsdale Inquirer, Number 13, 7 February 1920.)

Machen’s concern only grew stronger after his own denomination, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, adopted the Auburn Affirmation in 1924. Intended by its authors and signatories as a statement in favor of freedom of conscience and the congregational governance at the heart of Presbyterian polity, Machen and other critics saw the Affirmation as a rejection of the authority of the Bible and an abandonment of traditional Reformed doctrine. For the next several years, Machen would work to prevent this sort of theological pluralism from prevailing at the seminary and in American Christianity more broadly. Although often labeled as a fundamentalist for his staunch adherence to Biblical inerrancy and other traditional orthodox doctrines, Machen wrote:

I never call myself a “Fundamentalist.” There is indeed, no inherent objection to the term; and if the disjunction is between “Fundamentalism” and “Modernism,” then I am willing to call myself a Fundamentalist of the most pronounced type. But after all, what I prefer to call myself is not a “Fundamentalist” but a “Calvinist”—that is, an adherent of the Reformed Faith. As such I regard myself as standing in the great central current of the Church’s life—the current which flows down from the Word of God through Augustine and Calvin, and which has found noteworthy expression in America in the great tradition represented by Charles Hodge and Benjamin Breckenridge Warfield and the other representatives of the “Princeton School.” (Machen to F.E. Robinson, Esq., President of the Bryan University Memorial Association, June 25, 1927. Reprinted in THE PRESBYTERIAN, vol. 97, no. 27, July 7, 1927)

When, in 1929, a reorganization of the Seminary’s administration allowed for the inclusion of not only liberal, but also non-Reformed professors on the faculty, Machen and three other members of the faculty (Robert Dick Wilson, Oswald T. Allis, and Cornelius Van Til) left to found Westminster Theological Seminary in nearby Philadelphia.

Machen’s Church Trial

Machen’s efforts to stem the tide of modernist heresy in the Presbyterian church did not end with his retreat from Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1933, after he became convinced that the official missions activities of the Presbyterian Church were more in keeping with the teachings of modernist philosophy than Christian orthodoxy, Machen founded the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions. The General Assembly of the PC(USA) accused Machen of undermining the denomination’s efforts and ordered him to disassociate himself from the Independent Board. When Machen refused, on the grounds of conscience, he was brought before a church court in the New Brunswick Presbytery for a disciplinary hearing.

Clipping from an unknown newspaper. Image provided by the PCA Historical Center, St. Louis, MO. Used by permission.

Machen’s trial, held at the First Presbyterian Church in nearby Trenton, NJ, garnered nationwide attention; it was reported in the major newspapers of Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, as well as in Time Magazine (Monday, Mar. 11, 1935). The irony of Machen’s position–being harried out of a denomination that only ten years earlier had ‘affirmed’ the primacy of individual conscience to scripture–was not lost on outside observers who pointed to the trial as a watershed moment in the history of American Christianity. Indeed, two years after Machen’s trial (and subsequent suspension from the PC(USA), followed by his departure from the denomination to found the Orthodox Presbyterian Church), satirist and cultural commentator H. L. Mencken–normally quite critical of Christianity–applauded the theologian for his astute grasp of the peril presented to the church by modernism, and for the logical tenacity with which Machen defended his beliefs.

He [Machen] saw clearly that the only effects that could follow diluting and polluting Christianity in the Modernist manner would be its complete abandonment and ruin. Either it was true or it was not true. If, as he believed, it was true, then there could be no compromise with persons who sought to whittle away its essential postulates, however respectable their motives. (H. L. Mencken, “Dr. Fundamentalis,” Baltimore Evening Sun 18 January 1937, 2nd Section, p. 15.)

As Mencken observed, for a man of Machen’s faith and learning, there had been literally no other course to take.