The Catholic Church in the New Republic

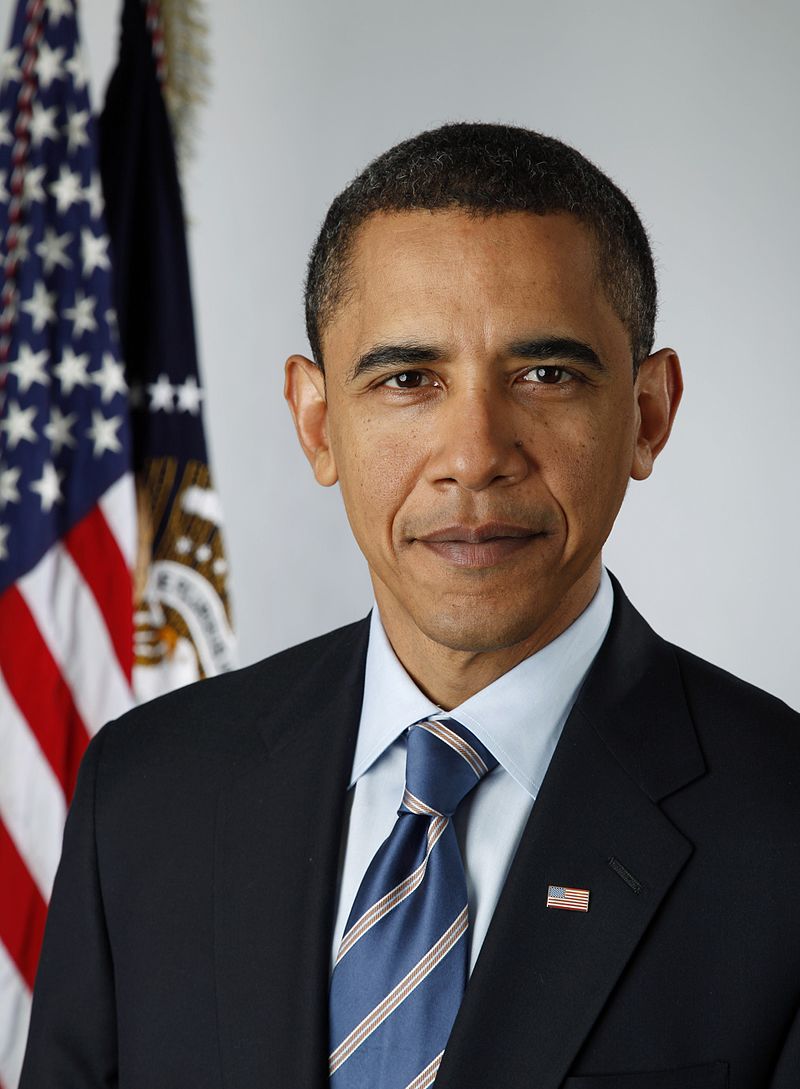

Archbishop John Carroll

June 27, 1783

On June 27, 1783, two months after the Confederation Congress approved the peace treaty that ended the Revolutionary War, a small group of American Catholic clergy met in Whitemarsh, Maryland to discuss how to organize the local governance of the Catholic Church in America. Led by the Reverend John Carroll, they were eager to promote the growth of the church in the newly independent republic.

The first efforts to organize the American governance of the Roman Catholic Church began 225 years ago, on June 27, 1783, at a meeting of six priests in Whitemarsh, Maryland. American independence having been achieved, these Catholic clergymen wished to be governed no longer through an ecclesiastical authority based in England but through one based in the United States. The Reverend John Carroll emerged as leader of this effort; within a year he would become ecclesiastical head of the Roman Catholic Church in the USA.

Archbishop John Carroll, from a lithograph by Lehman and Duval after a painting by Albert Newsam. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.,

LC-DIG-pga-06887.

The Education of John Carroll

Carroll was born in Upper Marlboro, Maryland in 1735. His ancestors had emigrated from England during the brief reign of James II, having been given a land grant through Lord Baltimore, the founder of the colony. John was the third son of Daniel Carroll, a successful merchant, and second cousin of Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration. Educated at home by his mother, herself a product of a convent school in Liège, he was sent at the age of twelve, along with his cousin Charles, to complete his education in a Jesuit school in French Flanders. He chose to enter the Jesuit order and was ordained a priest in 1769.

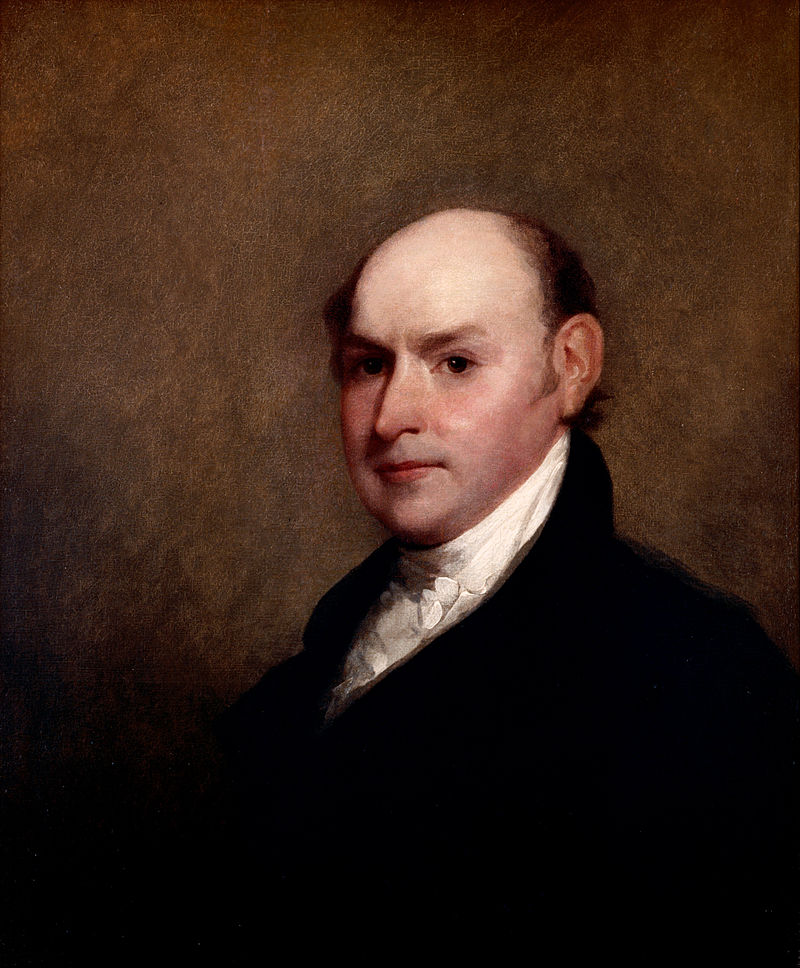

The cousin of John Carroll, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, signed the Declaration of Independence. Lithography by Childs and Inman, 1832, from a painting by T. Sully in 1826. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540. LC-DIG-pga-11753

Intellectually gifted, he was well suited to the teaching work of the Jesuit order and delayed returning to Maryland while serving as a professor of classics at the seminary in Liège where he himself had studied.

Carroll Returns to America

However, Pope Clement XIV’s decision in 1773 to suppress the Jesuit order prompted Carroll’s return home. After a brief sojourn in England, where he observed the rising tensions between England and the colonies, he set sail, arriving in Maryland in June 1774.

There he ministered as a priest to the Catholic population of Montgomery County, where his extended family lived, and oversaw the pastoral care of Catholics in Stafford County, Virginia, where his sisters had settled. As war with Britain began, he accompanied a delegation including Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase that attempted, fruitlessly, to persuade Canadian colonists to remain neutral in the conflict.

Freedom of Conscience in the New Republic Encourages Catholic Hopes for Growth of the Faith

Although Carroll took no other active part in the Revolution, like others in his family he supported the Patriot cause, believing that the Catholic faith could prosper in the new republic. (John’s brother Daniel helped to draft the Maryland state constitution, was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and served in the first Congress.) According to Archbishop Carroll’s biographer John Carroll Brent, the Archbishop himself wrote late in life a history of Roman Catholicism in America which recalled his confidence at the time of independence that freedom of conscience in the new republic would be “unqualified”:

The leading characters of the first . . . congress were . . . opposed to . . . vexation on the score of religion: and as they were perfectly acquainted with the maxims of the Catholics, they saw the injustice of persecuting them for adhering to their doctrines. . . . The Catholics evinced a desire, not less ardent than that of the protestants, to render the provinces independent of the mother country: and it was manifest that if they joined the common cause and exposed themselves to the common danger, they should be entitled to a participation in the common blessings which crowned their efforts.

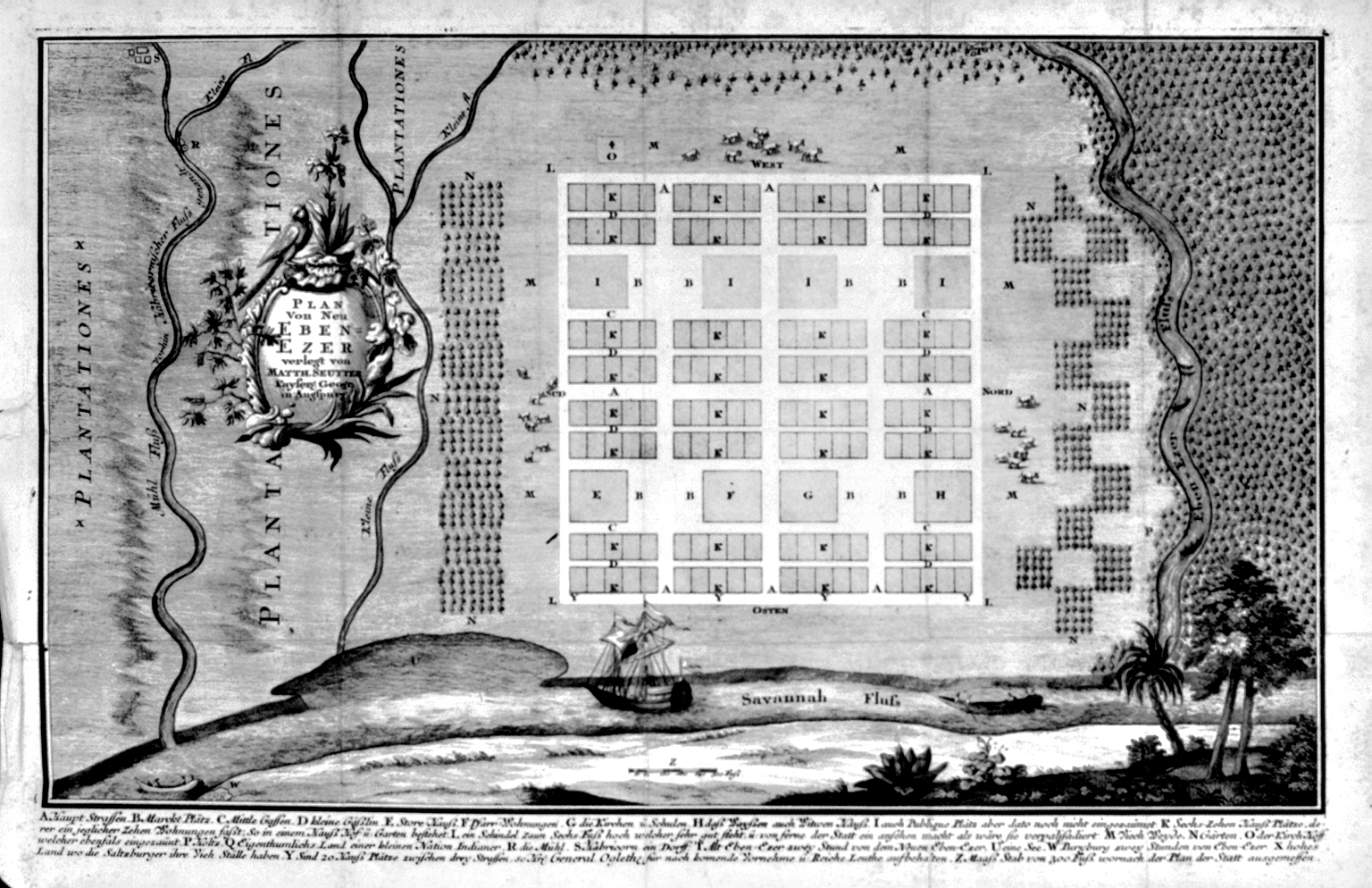

“Roman Catholic Cathedral of Baltimore, Cathedral Street, Baltimore, Independent City, MD,”photographed by E. H. Pickering in 1936 for the Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540, • HABS MD,4-BALT,41–1.

Applying to the Pope to be granted American governance, the small group of priests who first met in June 1783 soon recommended Carroll for the office, and the Pope confirmed Carroll as Superior of the Missions in the United States of North America in June of 1784. Carroll, writing to a friend in September 1783, had explained the motives of the requested change:

We are endeavoring to establish some regulations tending to perpetuate a succession of laborers in the vineyard, to preserve their morals, to prevent idleness, and to secure an equitable and frugal administration of our temporals. An immense field is opened to the zeal of the apostolic men. Universal toleration throughout this immense country [has prompted] innumerable Roman Catholics going and ready to go into the new regions bordering on the Mississippi, perhaps the finest in the world, [who are] impatiently clamorous for clergymen to attend them.

Carroll Defends Compatibility of Catholicism with Religious Freedom

Statue of Bishop John Carroll at the Baltimore Basilica, Baltimore, Maryland. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith between 1980 and 2006. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-highsm-16726 .

Despite Carroll’s confidence, others questioned the compatibility of Roman Catholicism and America’s new republican government. Shortly after assuming his role as Superior of the Missions in the United States, Carroll found it necessary to respond to an attack on the Roman Catholic Church as hostile to freedom of conscience, penned by an ex-Jesuit turned Episcopal priest, Charles Henry Wharton. Carroll responded with “An Address to the Roman Catholics of the United States of North America” in which he reconciled freedom of conscience with the goal of a unified Christian Church, writing that “General and equal toleration, by giving a free circulation to fair argument, is a most effectual method to bring all denominations of Christians to an unity of faith.” Published at Annapolis in 1784, this was the first work by an American Catholic to appear in the United States.

Growth of the American Catholic Church During the Early Republic

Baltimore Basilica, Baltimore, Maryland, photographed by Carol M. Highsmith between 1980 and 2006. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-highsm-16726.

Becoming Bishop of Baltimore in 1789, Carroll supervised the writing of canon law at the synod of 1791, founded the Sulpician seminary in Baltimore to train American priests, and in 1792 prevailed on President George Washington to persuade Congress to allocate federal funds for Catholic missionaries to the Native Americans in the West. In 1806, Carroll laid the cornerstone of Baltimore Cathedral. Until 1808, when four new Catholic sees were established in the US—in Boston, Philadelphia, New York and Bardstown, Kentucky—the entire American Catholic Church was governed from Baltimore. Carroll was elevated again to a position of preeminence when named Archbishop of Baltimore in 1811.

Archbishop Carroll died in 1815. During the thirty years of Carroll’s leadership of the Roman Catholic Church in America, the Catholic population grew from an estimated 20,000 to about 200,000.

Notes

Citation

O’Donovan, Louis. “John Carroll.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 27 Jun. 2018

John Carroll Brent, Biographical Sketch of the Most Reverend John Carroll, First Archbishop of Baltimore: With Select Portions of His Writing. Baltimore: John Murphy, 1843. Reissued by Leopold Classic Library.