YWCA in San Francisco’s Chinatown: Welcoming Immigrant Women

San Francisco, CA

1932-Present

As the oldest and largest multicultural women’s organization in the world, the YWCA—Young Women’s Christian Association—has often been at the forefront of efforts to help women lift themselves out of poverty. In the US, it has spearheaded efforts to welcome immigrants and combat racial discrimination.

The YWCA Girls Camp at Asilomar in 1916

The YWCA and its predecessor for men, the YMCA, began in England in the mid-nineteenth century, in large part as a response to industrialization, which some Christians saw as hindering the full moral and spiritual development of individuals. As young people from rural areas streamed into factory work in London, a group of Christian women worried about the physical and moral security of young women in the tough urban environment formed a prayer union. This led them, in 1855, to found an organization that would provide safe housing to the young migrants. In 1858, YWCAs were established Boston and New York. A YWCA boarding house for young women opened in New York City in 1860, and soon similar establishments were opened in other urban areas.

Dining Hall Designed by Julia Morgan for Asilomar Conference Center

Women who were for the first time separated from their families’ protection and exposed to the wearying regimen of 12-hour workdays were particularly in need of safe housing and supervised social activities (Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie offers the classic depiction of the young rural woman’s vulnerability to the city’s vices). Leaders of the YWCA soon recognized other needs: classes in typewriting and money management; employment bureaus; and, by the early 20th century, bilingual instruction for immigrant women. YWCA organizations strove to meet the needs of diverse populations, in the 1890s opening in Dayton, Ohio the first branch for African American women and in Oklahoma the first for Native American women. Until the mid-twentieth century, the organization restricted interracial programming to special conferences, an early instance taking place in Louisville, KY in 1915. Yet it adopted an interracial charter in 1948, eight years before the Supreme Court decision on school integration in Brown v. Board of Education.

Architect Julia Morgan’s Designs for YWCA Facilities in California

Merrill Hall, the chapel at Asilomar

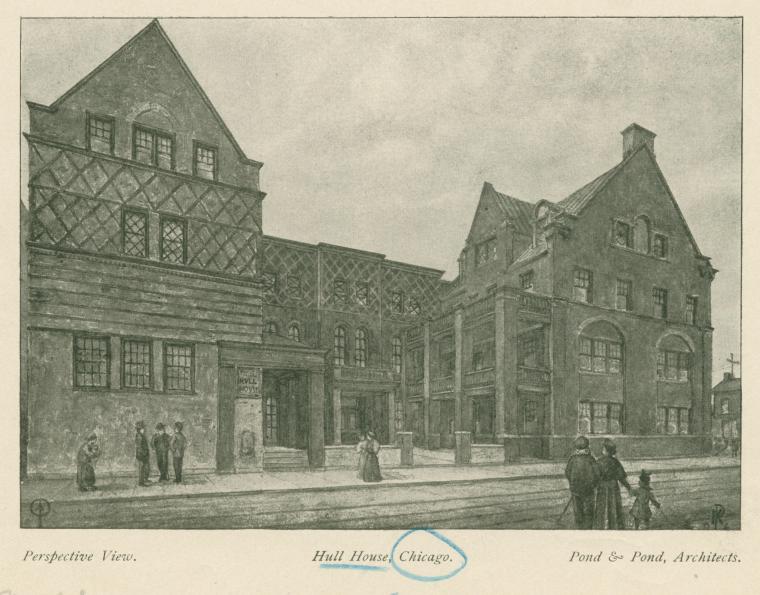

In California, a pioneer female architect renowned for her cost-effective and functional designs worked frequently with YWCAs to construct facilities. Julia Morgan’s design for a YWCA leadership camp on the Monterey peninsula housed summer retreats and conferences for thousands of young women between 1913 and 1933. Named Asilomar, a coinage from Spanish meaning “refuge by the sea,” it was built as a series of graceful “Arts and Crafts” style structures using local redwood and limestone. (Today it is a California state park.)

Many of Morgan’s commissions came from patrons such as Phoebe Apperson Hearst, Ellen Browning Scripps, Mrs. Warren Olney, and Mary Sroufe Merrill, all of whom helped fund Asilomar. Having risen to wealth through marriage or career, these women now wanted to promote the education of other women. They recruited her for other projects, including a YWCA building for the Chinese American community in San Francisco completed in 1932.

Front door of the YWCA building in Chinatown neighborhood of San Francisco

A YWCA for San Franciso’s Chinese American Community

Because racial attitudes of the time dictated that YWCA facilities be segregated, the Chinese American facility stands in graceful, curving contrast to a taller, plainer YWCA lodging for white women. Morgan worked with her clients to integrate Chinese spiritual motifs into the exterior and interior design. She designed decorative screens on the exterior windows and gave upward-curved eaves to the two towers of the building, since these design elements are thought to thwart access to evil spirits, who according to traditional belief travel in straight lines.

At the center of one window screen is a lotus; at another, a dragon—a symbol, among other things, of adaptability and transformation. A larger, colorful dragon decorates the tiled floor of an interior entrance hall. An open-roofed courtyard, featuring a pond stocked with koi, the fish that symbolizes wealth and success, provides a tranquil place for meditation.

Today the building houses the Chinese Historical Society and Museum of San Francisco.

Also in 1932, Morgan designed a YWCA facility for San Francisco’s Japanese American residents, including an auditorium with a Noh theater stage and an adjoining alcove or tokonoma for performing the tea ceremony.